Australia’s highest court – in confirming that the waiver of statutory consumer protections by contract or agreement is permissible – has paved the way for a mortgagee to collect nearly $8 mil for a $270k debt after 20 years.

The ruling approves a “contracting out” clause that prohibited a mortgagor from pleading a limitation defence against any loan debt recovery action taken by the mortgagee.

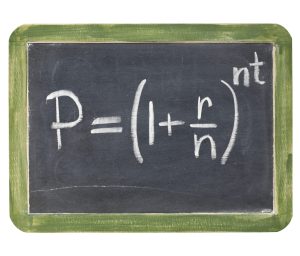

In July 1998, Matthew Price and other members of the Price family granted mortgages over land at Minden, Rosewood and Tallegalla in favour of Law Partners Mortgages to secure a 12 month $320k loan at 16.25% interest compounding monthly.

After the borrowers failed to repay monies in July 1999, an extension for repayment was agreed until July 2000 but the borrower defaulted on the repayment once again.

In November 2000, part of the mortgaged land was sold for $116k and the proceeds paid to the mortgagee reduced the principal by $50k.

By April 2001, after accounting for adjustments, the loan debt was $270k. Thereafter the appellants made no further repayments.

LPM subsequently sold the loan under longstanding default to “a small pension fund” the trustees of which were the respondents to the appeal.

In 2017, the trustees – Christine and Kerry Spoor – initiated proceedings in the Supreme Court claiming over $4 million as the debt due under the mortgage it had acquired.

The Price family defended the recovery action on the basis that the mortgagee was statute barred from ‘no later than 30 April 2013’ from pursuing an ‘action for debt or enforcement’ and enforcing rights under both mortgages pursuant to ss 10, 13, and 26 of the Limitation of Actions Act (Qld).

The Prices also contended that LAA s 24 had extinguished the mortgagee’s title. They argued that s 24 operated automatically at the end of the limitation period and was independent of s 13 which established a limitation period of 12 years in actions to recover land.

Justice Jean Dalton agreed at trial, that the respondents’ rights to an interest in the land as mortgagee had been extinguished.

The mortgagee asserted however that by operation of cl 24 in both mortgages – which stipulated that the borrowers would not plead a limitation defence – they had breached the mortgage agreement by doing so.

They also asserted the borrowers should be ‘estopped from pleading a defence’ under the LAA.

Justice Dalton quickly dismissed the estoppel claim and held that “contracting out” clauses, like cl 24, are generally valid.

She concluded while it is not possible to contract to exclude the “extinguishment of title” consequences of LAA s 24(1) this did not prevent the lender recovering monies owed.

Ultimately though she ruled against the lender by concluding cl 24 was too vague to prevent the operation of the LAA as a block to the recovery action.

Unhappy with the outcome, the mortgagee appealed the decision to the Queensland Court of Appeal who found in its favour.

When the matter came before the High Court a further issue – whether an agreement not to plead a limitation defence was contrary to public policy – was ventilated.

To support its argument, the Price family submitted that an individual ‘cannot contract out of the defences conferred’ by the Act because parliament intended ‘a person should not have this freedom’ having regard to the purpose and scheme’ of the Act.

Noting the dearth of clear authority that directly deals with the question of whether a contractual provision not to plead a limitation defence is ‘void against public policy’ the court reasoned that the rights could be waived if they were private in nature.

In doing so it approved the obiter comments of Mason CJ in Commonwealth v Verwayen that a person may waive statutory defences unless the statutes prohibits contracting out or “the scope and policy of that Act” is “not for the benefit of any individuals or body of individuals, but for considerations of the State”’.

Thus it is not contrary to public policy for a party to an agreement surrender a statutory right in their favour as an individual and such an agreement was enforceable.

The Court also rejected the argument – and Justice Dalton’s conclusion – that the mortgagee’s title to the land was extinguished by the operation of LAA s 24. That section operated no differently than did s 13, it concluded.

Turning to the construction of cl 24 of the mortgages, the court decided it should be ‘determined objectively by what reasonable persons in the position of the parties can be taken by adopting the words to have meant’.

Looking at the text of the document, the ‘surrounding circumstances’ known to both parties, and the ‘purpose and objective of the transaction’, the clause was – contrary to the borrowers’ submission that ”strong words” were needed to contract out of a private benefit – sufficiently precise to effect the ‘contracting out’ that was intended.

“Clause 24 is expressed to apply to all statutes affecting the mortgagee’s rights and remedies and the obligations of the mortgagor, ” wrote the chief justice and Justice Edelman in their lead joint judgment. “The effects spoken of include the defeat or extinguishment of rights [and] …the concluding words of the clause, ‘insofar as this can lawfully be done’, takes the matter no further”.

Justices Gageler and Gordon observed that cl 24 did not purport to operate as an ‘immediate renunciation or abandonment of the statutory rights’ to plead the defences in LAA ss 10 and 13, but rather was a contract not to rely on the limitation provisions at any time up to the judgment”.

The High Court dismissed the appeal entitling the Spoors to recover the $4 mil plus monthly compounding interest at 16.25% from 2017 until the date of repayment.

Price v Spoor [2021] HCA 20 Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman, Steward JJ 23 June 2021